I've been migrating my circuits out of the breadboard and into soldered form. I'm also hooking up speakers so that my sound generating circuits are ready for installation in a sculpture of Virginia's nocturnal ecosystem. Because most of my circuits use a custom piezo electric speaker (built with my own amplifier board), I have to install each piezo element into a physical housing... and there's some interesting "play" here. One electronic signal can generate many different sounds depending upon the speaker's physical design. Here's a video of me testing various installations of a piezo element for an insect that makes a steady background noise.

It's cool to experiment with the interface between electrical signal and material properties. It's also critical to get it right, or else the piezo element will make a horrible rattling or screeching. Even a tiny drop of glue (to fix the piezo element in place) will alter the sound quality --usually the pitch-- and superglue can sound different from rubber cement or hot glue or tape. All of this is no news to a human musician, who knows that a note ill-played (even slightly) is a fail, and teensy subtleties often make the difference between average sound quality and genius.

It is interesting to wonder what makes animals of the same species sound different in nature: is it their electrical impulse or their physical form? (Is it their schematic, their CAD file, or their bill of materials?) Members of the same species inherit the same circuit design as well as physique. External physical factors, such as climate, have some degree of influence over material properties of the body --for example, a dehydrated cricket sounds differently than the same cricket wet with rain; a fat frog sings a different tune than the same frog skinny; and so on and so forth. We also know that "animal circuits" are sensitive to electromagnetic fields, and capacitive coupling undoubtedly affects individuals in close proximity. I suspect that physical factors play a greater role in the variability of an individual's song if but for no other reason because birds sound the same whether they are sitting on a tree branch or an electrical transformer (at least, I think they do). PS: Eventually I will tackle the challenge of bird song, but their vocal complexity requires more computation... which is why I have started with insects.

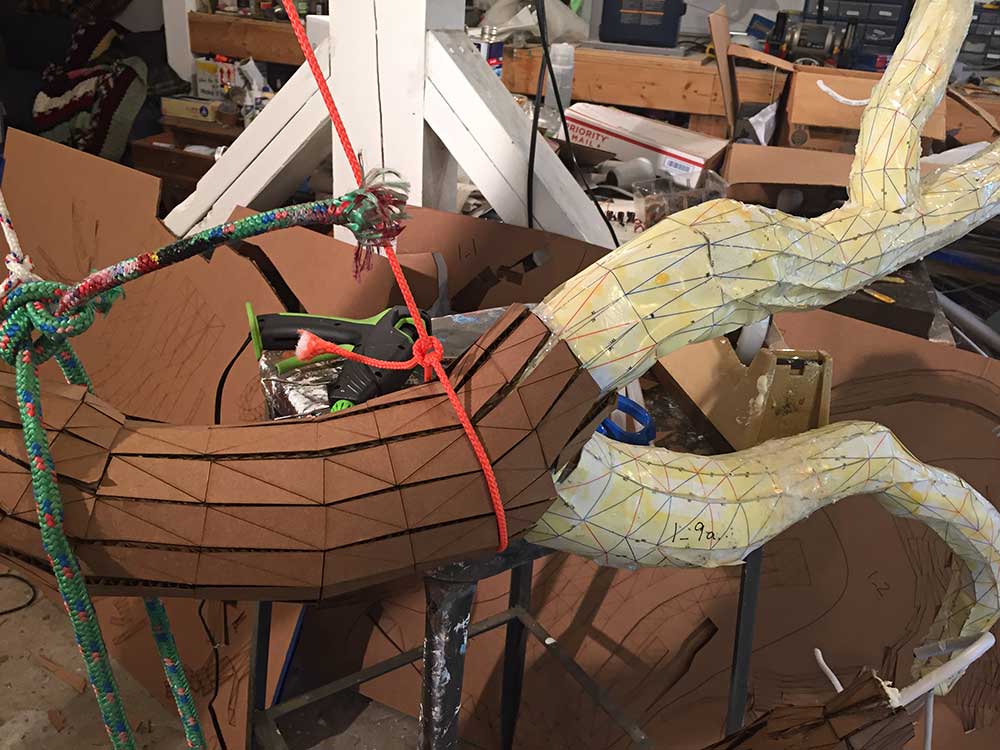

To end this log, I leave you with one more video clip of my "background noise" insect. Here it is with a plastic spool installed over the piezo (now painted green, black, and white). The soldered perfboard is embedded in a cardboard cutout that is painted to look like a forest creature sounds. Soon, this mixed media object will be joined with other embellished animal circuits to build a vignette of nocturnal musicians.