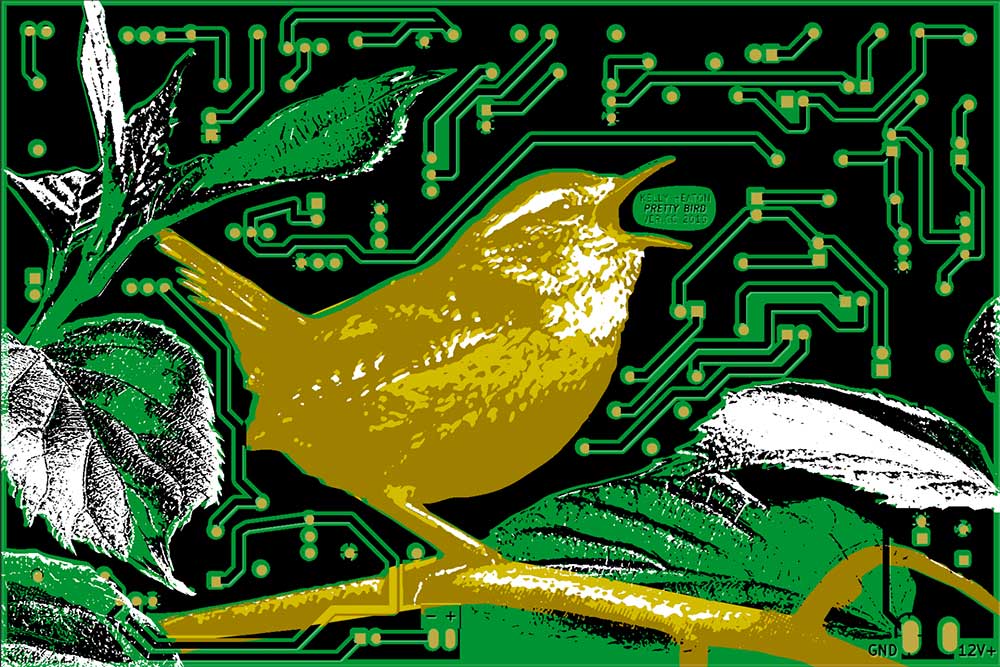

Here it is at last: my edition of 150 printed circuit boards and associated components, “Pretty Bird ver. CC,” 2019. This multiple was commissioned by Creative Capital for their 20th summer retreat celebration. I designed the artistic circuit using discrete hardware to generate waveforms from a 12 volt DC power supply, visible as blinking LEDs and audible through an 8 ohm speaker. Under the right lighting conditions, the sound is reminiscent of “pretty bird,” a song of the Carolia wren. There are no audio recordings or software algorithms involved in this effect — it’s entirely analog electronic. In the upper left corner of the circuit is a light-dependent resistor that affects the frequency of a negator oscillator, as I demonstrate in the video by changing the ambient light. It’s fascinating to me that a small quantity of common transistors, resistors, capacitors, and diodes can create vibrations that are so life-like. Similarity or simulacrum? The spark of life.

creative capital

Pretty Bird CC test run video /

Pretty Bird ver.CC 2019 test run /

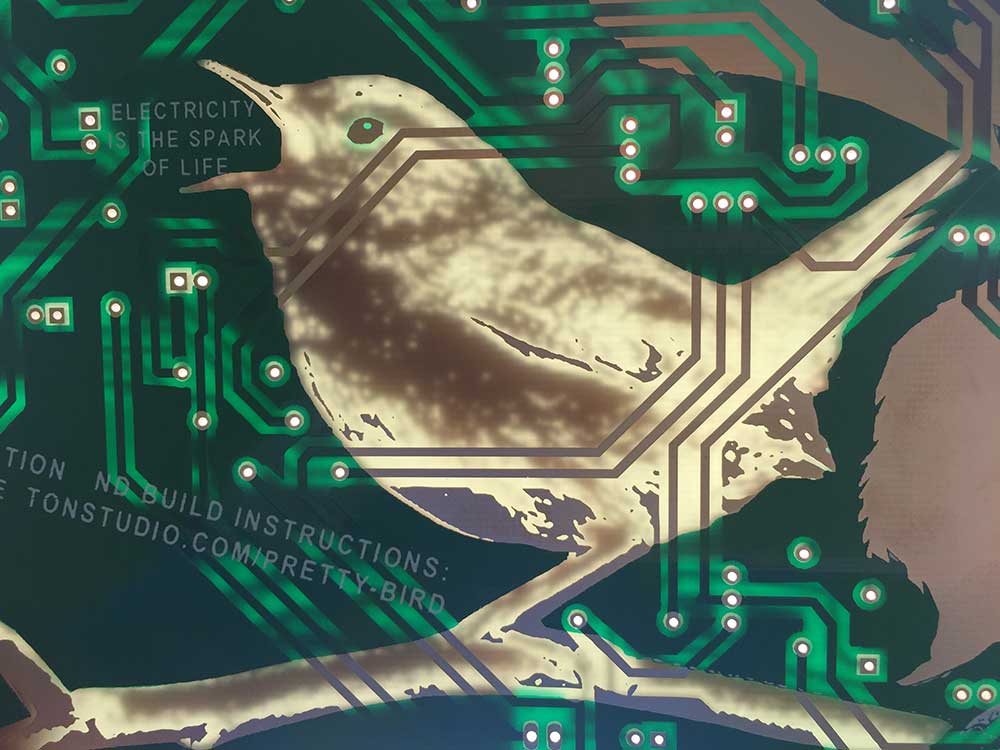

My first run of boards came in this week. I am pleased to report that the circuit works as intended (sings an analog electronic song). I’ll post video of that soon, but for now, some photos of the pretty board. I used gold-plated copper and solder mask to achieve a watermark effect, as you can see in some of these pictures. These boards (along with components to solder) will be given to attendees at Creative Capital’s 2019 retreat in June.

Pretty bird process /

Various images from the process to design a pretty bird printed circuit board for manufacture. April, 2019

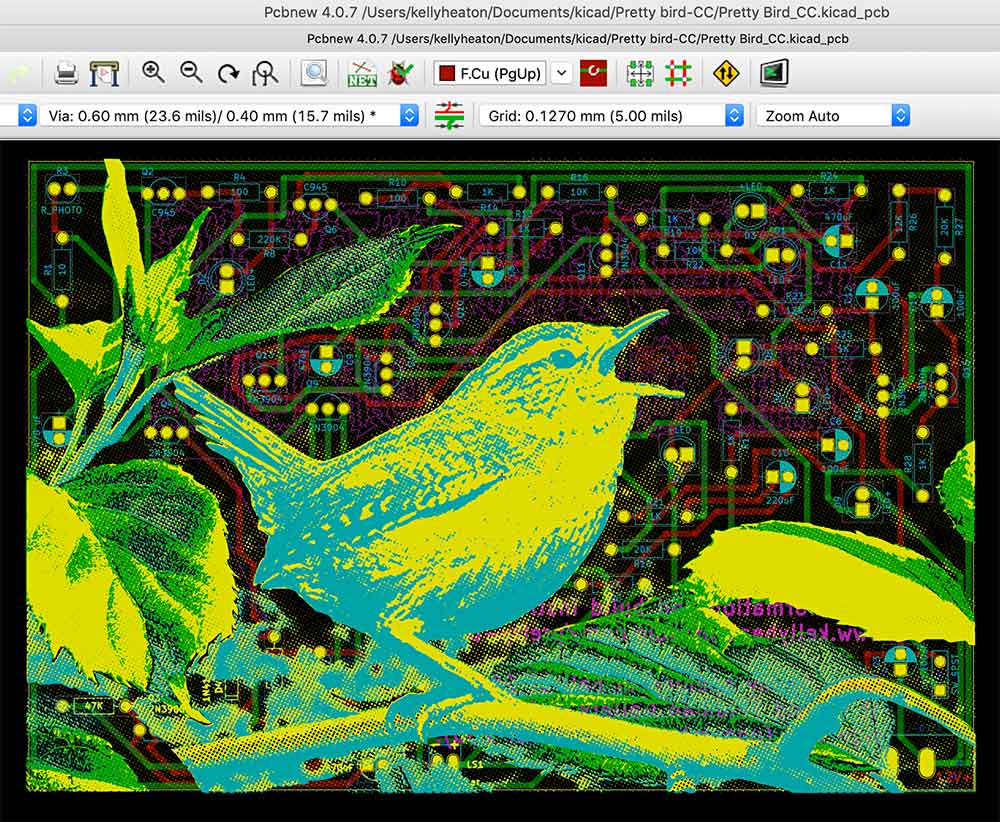

Pretty bird PCB /

2019 circuit board designed in KiCad (colors correspond to KiCad layers - not my choosing, but interesting op art effect). The circuit sings a simple “pretty bird” song as demonstrated in the following video…

Tortuga Escondida Fellowship || Akumal, Mexico /

I’m back from a transformative five weeks in the Yucatán peninsula. This blog entry has been difficult for me to write because I’ve got so much material and it’s not easy to articulate. I will try to present my impressions of living in Mexico, the quirks of electrical engineering in a tropical jungle, my work with the people of Akumal pueblo, and how this experience has changed my life —at least, in a preliminary view.

The story and accomplishments that I describe were thanks to many supporters: the staff of Tortuga Escondida for inviting me to be a resident; GoFundMe donors and Creative Capital for making my work financially possible; the Akumal Arts Festival for supplying me with paint, a blank wall, and so much more; the Centro Comunitario de Akumal Pueblo for accepting my electronics donation and empowering the community to learn new skills; and to my new friends in Mexico who received me with open arms and showed me a fluid world of magic. From the bottom of my heart, thank you to everyone who made this giant, messy “ball of happiness” possible. You have given me a life-changing experience that continues to unfold with powerful momentum.

Jaguar spirit holding the fire during a Mayan cacao ceremony, November 2018. Yucatán Mayans say that there are as many portals in the universe as there are spots on a jaguar.

My original intention for traveling to Mexico was to study the sounds of nature in a tropical jungle, feel the local energy, and build electrified works of art based on my experience. I also wanted to teach local residents about electricity and circuit design, hopefully inspiring some new “makers” in the small town of Akumal, Mexico, where tourism is the predominant industry and other educational opportunities are sparse. I am pleased to report that I achieved these goals and much more, but my path was not straightforward.

Tortuga Escondida residency center is located in a tropical jungle several pot-hole-dirt-road kilometers outside of Akumal pueblo. If not for the occasional outing, you would never know that Akumal is nearby, much less the overdeveloped Mayan Riveria coastline. Isolation in the jungle gave me plenty of natural inspiration and afforded me headspace to tackle a new challenge: circuits that sing like birds. I created three new works of electronic art thanks to and despite the wonderfully weird circumstances down there. Electrical engineering in a tropical jungle is challenging for many reasons, some of which I predicted (wildlife, limited supplies, high humidity) and some surprises (power fluctuations, mischievous house spirits, no package delivery, unreliable connectivity). I forgot a few supplies and inadvertently damaged others that were thankfully replenished by friends of friends visiting from the States —bless them, because it can take weeks or months via a “mule” to acquire something that isn’t locally available. Still, my oscilloscope abruptly died at the end of week two, even though it was unplugged and stored in a sheltered location with air conditioning. Locals claimed it was the work of an "Alux," pronounced "Aloosh", a Mayan nature spirit similar to an elf or house goblin. Apparently, the Alux that lives on the grounds of Tortuga Escondida likes to sabotage electronic devices and has killed so many hot water heaters that they’ve given up on replacements. They’ve even consulted an Alux removal specialist (a real vocation in this part of the world). Anyway, I managed without an oscilloscope and hot showers, and below are images of the works that I produced with my make-shift electronics bench at Tortuga Escondida.

Above: three electrified watercolor studies of birds in the Yucatán Peninsula. Tortuga Escondida’s caretaker generously built three wooden frames to protect my work (one frame not shown). Near Akumal, Mexico, 2018

Thanks to supporters of my GoFundMe project, “Hacking Nature’s Musicians | Mexico,” I donated the electronics bench that I used to create these bird studies to the Akumal Community Center, where several high school students and professors have been appointed as “electrical engineering champions.” Until now, there hasn’t been any sort of electronics hacking equipment in Akumal for students to learn about circuit design and safely experiment with electricity. Local educators determined that the pueblo’s community center was the best location for an electronics bench because the school cycles through three different age groups in a day, and it’s a pretty chaotic environment.

Fortunately, another electronic artist (Jackie Neon) came to town for the Akumal Arts Festival, and she helped me to lay a crucial foundation of interest and understanding. Jackie hosted several all-age, all-skill-level workshops called Sense Circuits, in which participants learned how to connect an LED or motor to a battery using conductive (and resistive) thread. I was really impressed by her workshop design because it’s not easy to teach total beginners about electronics without the risk of breaking components. Based on community response to Jackie’s Sense Circuit workshops, I was able to identify members of the community who have the interest and discipline to go further with electrical engineering. I hosted a two-hour workshop in mediocre Spanish to explain the equipment that I donated to the community. I offered tips for independent study, including how to search for schematics on the Internet, and the importance of studying data sheets. One participant was so enthusiastic in his desire to learn electrical engineering that he bamboozled me with hard questions. I was thrilled to know that this equipment will be appreciated and used.

Besides my interactions with Jackie Neon and her Sense Circuits workshops, I was only vaguely aware that the inaugural Akumal Arts Festival would happen during my residency because painting a mural wasn’t part of my fellowship proposal. So much for plans. About the time that my oscilloscope died, after two intense weeks of studying birds and building circuits in the shady jungle (like a pasty, hunchbacked golem), a friend drove me to Akumal to see the first mural in progress. It was a sunny day and the athletic, tan, happy street artist was covered in sweat, bright colors, and grime. The impression hit me like a ton of bricks: this artist is having way more fun than I am. Painting a street mural seemed like the perfect way to balance out my endless hours of cerebral circuit bending. Plus, what an opportunity for me to make a difference in the landscape of Akumal pueblo —a dirty, unattractive town at the time of my arrival in mid-October. And so it happened: I befriended an Akumal resident who offered to assist me, selected a wall (actually two walls that join in a corner), quickly sketched a design, ordered house paint, and put myself to the task of creating my first-ever work of street art, “Dos Dioses de la Electricidad.” The next five days were filthy and exhausting to an extreme, especially given my lack of physical fitness and reconstructive hip surgery two months prior, and painting on a ladder in tropical heat is not trivial. But —wow— what an incredible experience to work in the streets, meet curious strangers, talk to the police, witness someone be put in jail, hear a noisy Mexican town, and explain the meaning of my art in a foreign language. More than anything, truly beyond what I can put into words, I was blown away by the utter transformation that took place in Akumal. More than 80 artists came from all over the world to paint the town, and the energy rose in a palpable crescendo. Cinderblock buildings, an empty square, and trash-filled streets were transformed into an outdoor art exhibition with clean sidewalks, a new playground, and the beginnings of a proper Zócalo. At the closing ceremony —scented with sacred copal, high on sugary churros, and drunk on a feeling of civic love— we were all laughing and crying and gasping in disbelief at our good fortune to be part of an experience so uncommonly beautiful. I am convinced of the power of art to change lives because I’ve seen it happen beyond a shadow of a doubt.

Above, left to right: corner of the Akumal Delegacion Building as I first found it; a concrete pillar painted by my friend and helper, Patricia Delfin (Mayan long calendar date format for “November 9, 2018”); a dirty and triumphant me at the conclusion of the mural.

As far as I can tell, Mexico is a place where things don’t usually go according to plan. “Expect the unexpected” should be the country’s motto —and I say this with the greatest admiration— for while Mexico’s surprises were initially frightening or aggravating to me, I came to accept the steady drip of unexpected events as medicine for my generalized anxiety disorder —more therapeutic than any treatment I’ve encountered in my decades-long journey through the western medical system. Living in Mexico forced me to find freedom and humor in my loss of control, an enduring lesson that far outweighs whatever discomfort I may have experienced in the short-term. I’m not saying that it’s easy for me to flow with my environment. I’m saying that resisting a strong current feels worse, and flowing offers the added benefit of inner peace. Apparently some visitors won’t let go of their desire for control and become chronically pissed off (I met several expats in this toxic state), but we won’t go there except to say that hating reality is futile. One must accept reality or work for change. Where struggle is concerned, I like the wisdom that Don Juan imparts to Carlos Castenda in “A Separate Reality,”

“The spirit of a warrior is not geared to indulging and complaining, nor is it geared to winning or losing. The spirit of a warrior is geared only to struggle, and every struggle is a warrior’s last battle on earth. Thus the outcome matters very little to him. In his last battle on earth a warrior lets his spirit flow free and clear. And as he wages his battle, knowing that his intent is impeccable, a warrior laughs and laughs.”

To be sure, Mexico is not an easy place to live and work and sometimes it’s downright harsh —hardly a laughing matter. But in my recent experience, most Mexican nuisances were harmless: enormous tarantulas crawling peacefully through in my dormitory in the evening, to disappear by next morning; a voracious combination of humidity and voltage spikes that ate away my soldering iron, leaving me to weld with a tip as blunt as my index finger; and the giant pile of sand in front of the police station, with no obvious owner or purpose, which tripped me repeatedly during the week that I painted my Akumal mural (despite polite requests for removal), and was suddenly shoveled away by an incarcerated drunk the day after I finished work. And then there was the negative energy oozing through the wall opposite the jail cell which caused half of my mural to peel until I performed an impromptu healing ceremony that stopped the peeling but gave me a roaring head cold. (I followed the advice of a local healer and tried to expel my flu with a temezcal ceremony, but suffered a panic attack and was compelled to crawl over the bodies of multiple acquaintances on my premature exit from the sweat lodge.) To ensure that I wouldn’t lose my temper over daily challenges, I was fortified each night with cold showers, scorpions in my sink, and friendly but dutiful guard dogs who barked at 3am, or 5am, and maybe both times and then some. Barking dogs were mitigated with ear plugs, but waking to thousands of ants migrating across my room, bed, and body —that required a new level of personal zen.

Some triggers of fear in Mexico (above left to right): large hand-sized tarantula near the entrance to Tortuga Escondida; the Akumal jail cell; an entrance to Xibalba; the tree of life deep inside Balankanche cave near Chichen Itza

Surprises are not always hard to stomach. Oftentimes, Mexico is downright magical in the happiest sense of the word. I achieved fascinating results in my jungle-improvised electronics studio, and I even witnessed multiple species of birds singing in response to my chirping circuits. I gave my first electronics class in Spanish and had the distinct impression that I changed a man’s life. I made several life-long friends in less time than I spent maintaining distant, unsatisfying contact through social media. I managed to paint a large portion of my first street mural using a cheap roller that fell into the dirt repeatedly (i.e., once or twice a minute). I witnessed strangers open their hearts and give freely in a multi-cultural exchange that overcame grudges, judgement, and hierarchy. I used a paper map to navigate poetic roads across remote areas of the Yucatán peninsula. I met people who unabashedly believe in the existence of spirits, and I participated in five Mayan ceremonies. I climbed ancient pyramids and wondered why great civilizations were abandoned at least five hundred years before the Spanish arrived. I saw Morpho butterflies, Motmot birds, Tucans, Chacalacas, Flamingos, Howler monkeys, and giant Iguanas. I swam with sea turtles, heard strange owls, watched millions of bats fly in a vortex, and felt the presence of a jaguar. I stayed up all night in the jungle, sang a mixture of Mayan prayers, Christmas carols, and southern spirituals, confronted my fears in multiple sweat lodges, and descended into Xibalba four times. I left with the distinct impression that hardship is not something to be avoided, but embraced as a practice of spiritual growth, perhaps as the only way to cultivate openness to the truly good stuff in life —the stuff that money and convenience simply cannot buy.

Below are a few of my photographic impressions, although most of the magic I witnessed could not be easily captured. I will have to create works of art for that which words and cameras could not record.

Thank you again to everyone who made this amazing experience possible! Yum bo’otik.

The Raft of Medusa /

"The Raft of Medusa" (1 in a series of 5 unique works), 2017. 39.5" x 54.25" Archival inkjet print, silk screen, and acrylic on canvas

I created five unique versions of this print during my summer residency at Otis College of Art and Design. This work was made possible thanks to support from Creative Capital, Otis College of Art and Design, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, and volunteer models. "The Raft of Medusa" (1 of 5) will be donated to the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation 2017 auction to raise money for environmental defense and climate change activism. For more information about the auction, please contact Lisa at Schiff Fine Art (info@schifffineart.com or (646) 478-8561). For more information about other prints in this series of 5, please contact Marco Nocella at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts (marco@feldmangallery.com or 212-226-3232).

BACKGROUND

Painted in 1818-1819, Théodore Géricault’s “The Raft of the Medusa” is a masterpiece of human error, desperation, and resilience. I recreated this legendary artwork for the purpose of climate change activism. I used a raft made of trash, rising ocean levels, and a carbon-saturated atmosphere to situate 21st century people adrift on a dangerous sea that they largely ignore. One occupant of the raft looks distressed, but the others are preoccupied with their cells phones or focused on other people. My message is reinforced with sea snakes and electrical cords that remind us of Medusa, the mythological woman who was cursed by Athena for her insufferable vanity.

Above: details from The Raft of Medusa (1 of 5), 2017.

Below: Images from my process of creating "The Raft of Medusa" series of 5 unique prints. The first three images show the raft that I built from trash collected in Los Angeles. The people are volunteers who came separately to be photographed on the raft. Using Photoshop, I collaged everyone into a single, coherent composition that I printed onto canvas using an Epson archival inkjet printer. Next, I created films for each design and color layer of silk screen. I burned a series of screens that I used to print "spot colors" of designs onto the canvas that add depth and texture to the rising ocean, the carbon-saturated sky, the electrical cords, and the serpents of Medusa. I screen-printed onto my inkjet print because I wanted to make nature and electricity literally encroach upon the raft and its occupants - who represent all of human civilization. Sadly, humanity is largely self-absorbed and unresponsive to the crisis of climate change.

Above top row: three volunteers from the community of Otis College of Art and Design who individually posed for The Raft of Medusa (2017)

Above middle row (left to right): my digital master file, selecting negatives for burning screens, applying photo emulsion to a silk screen. Photos of me working on the piece are courtesy of Antonia Jones of Los Angeles.

Above bottom row (left to right): rinsing my screen to reveal an image, registering my canvas prior to printing, pulling ink through the screen to print on the canvas. Photos courtesy of Antonia Jones of Los Angeles.

news: wave and particle group show opens 02/14/15 /

I am pleased to announce that work from Live Pelt (2003) will be included in a group show to celebrate the 15th Anniversary of Creative Capital. Wave and Particle opens February 14th (reception 6-8pm) and runs through March 21. Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, 31 Mercer Street NYC 10013. Open Tues through Saturday 10am - 6pm or by appointment.

http://blog.creative-capital.org/2015/02/ronald-feldman-fine-art-presents-wave-particle/