Amazing as the insects are, I'm not studying musical bugs because what's most remarkable to me --coming here from Virginia-- are the myriad species of birds. I've decided to see what I can do with the analog electrical engineering of bird song.

As a starting point, I built a version of the classic, "chirping canary" used in kitschy artificial nature scenes. Check out my files on Hackaday.io for an annotated version of this schematic, which is based on audio transformer oscillation. Basically, the surge in DC power that happens when you first turn the circuit on is capacitively coupled across the transformer and continues to fluctuate thanks to a transistor switch. If you change (or remove) certain capacitor values, the circuit stops oscillating and makes an unpleasant tone that can be very loud due to the current gain across the transformer.

I've made a first informal video showing how the sound changes when different parts of the circuit are modified (apologies in advanced for some unpleasant beeps - don't wear headphones).

Next, I built a few astable multivibrators and connected them to various aspects of the sound-generating circuit in order to make the chirp sound more like a bird song. Some of my tests are documented in a second video that you can watch on Vimeo.

Watch the green LEDs (and follow the white wires) to get a sense for what the astable multivibrators are doing.

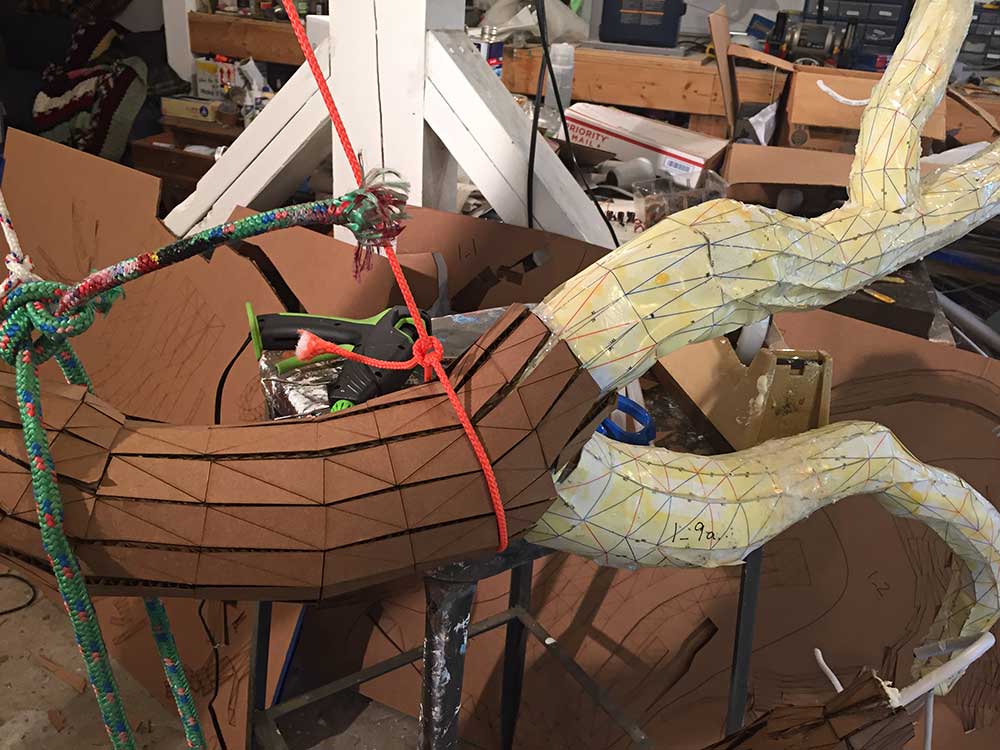

Birds are very clever singer-songwriters, so it's going to take a lot more work on tempo and pitch variation to get interesting songs. I plan to try numerous strategies to generate voice quality because I want to build a jungle of different bird circuits ranging from sparrows to whippoorwills to parrots to owls to a Resplendent Quetzal, relative of the legendary Mayan Plumed Serpent. If you have suggestions for circuits to try, I would be grateful.

So... not only do my bird electronics need work, I could use a new "avian speaker" design. It seems that piezo buzzers are better suited to insects, while 8 ohm speakers have higher bird fidelity. Initially, this observation puzzled me (and I'm still not clear) but I got some useful clues from the ingenious musician, Nicolas Bras. It's material physics: the thin, metal vibrations of a piezo disk have more in common with the chitin instrumentation of an invertebrate than the fleshy air bladder and vocal chords of a squawking bird. Some insects do force air through a membrane, like living kazoos, but crickets rely heavily on the idiophonic effects of leg or wing rubbing. The sound made by an idiophone is quite different than that of an aerophone or membranophone, like hitting a cymbal versus blowing through a reed, the latter of which happens when a bird forces air through its vocal cords. I searched the web for homemade instruments that behave like an aerophone with a membrane and found this cool "membranophone" video by tachionics.

As I did with my "insect-like" piezo, I'd like to build an electronically actuated speaker that has material properties more in common with a bird. I've got various 8 ohm speakers that are working for now, but I suspect that there's a better design to be made -- or at least some cool insights to discover in the process of trying. Again, your suggestions are greatly appreciated!

Stay tuned.